By Peter Sankoff, Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Alberta

Camille Labchuk, Director of Legal Advocacy, Animal Justice Canada

Earlier this month, Quebec tabled new animal protection legislation that makes it the first jurisdiction in Canada to recognize that animals are sentient beings with biological needs. Although this fact will seem obvious to anyone who has ever lived with an animal, stating it so boldly marks a major symbolic change for the law.

Still, in order to address the ongoing plight of animal suffering in Canada, symbolism is no longer enough. The biggest barrier to protecting our animals isn’t existing legislation, it’s the refusal to get serious about enforcing the animal protection laws we already have. In short, we need a change in mindset for those tasked with investigating and prosecuting these offences, and an infusion of resources to ensure that animals get the protection our laws say they deserve.

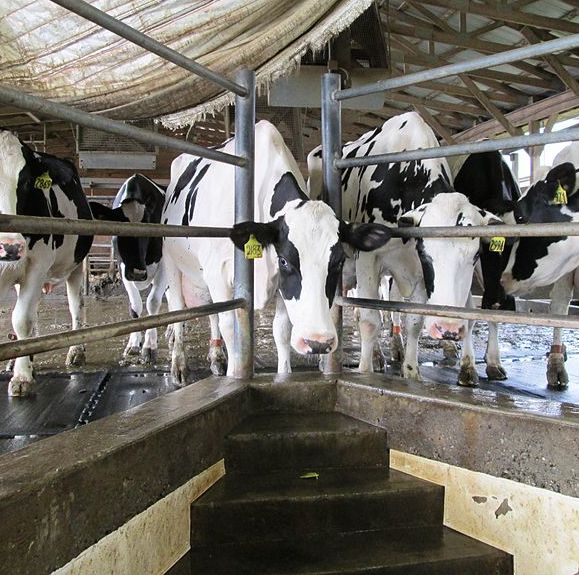

Quebec’s exciting move forward can be neatly juxtaposed against an unfortunate animal cruelty “anniversary.” Exactly one year ago last week, an undercover investigation airing on CTV National News exposed the horrific abuse of cows at a dairy farm in Chilliwack, British Columbia. On top of suffering from painful health ailments like open wounds and other injuries, the cows endured regular physical abuse, with employees using chains and other implements to viciously whip, punch, kick and beat them. Media coverage was intense and Canadians expressed outrage. There was talk of boycotts and major inquiries, while the farm owners professed contrition. Not surprisingly, the British Columbia SPCA quickly recommended that criminal charges be laid against the responsible parties.

One year later, things have gone eerily quiet. Despite the overwhelming evidence of torture and cruelty captured on film, no charges have been laid. Most alarmingly, we have had no explanation for the delay and the public is left in the dark as to whether anyone will ever be charged. In comparison, Jian Ghomeshi’s notorious sexual assault case went from allegations to charges in less than three months, a much more common time frame for criminal offending.

Sadly, the Chilliwack case follows a familiar pattern where the abuse of animals is concerned. All too often, investigations into animal cruelty turn into prolonged affairs, with prosecutions delayed or stopped altogether while a host of prosecutors decide whether charges are actually warranted. Why are prosecutors so reluctant to charge those who abuse animals, especially where this takes place on farms?

Some of the problem likely lies in the evidentiary nature of these cases. Prosecutors are used to having victims who can speak about the harm they endured, which is obviously not a possibility where animals are concerned. But perhaps it has more to do with the way crimes against animals are treated by the law. Animal cruelty offences are the only crimes investigated almost exclusively by a private charity. SPCA investigators operate at arm’s length, are terribly under-resourced, and in some jurisdictions must individually convince prosecutors of the merits of a case every time they recommend that charges be laid.

Federal regulations to protect farmed animals don’t fare much better. While these are enforced by the federal Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), the agency’s track record indicates that regulatory charges with the potential for punishment are brought as an absolutely last resort. The CFIA’s primary objective is food safety, not animal welfare, and at least one recent public example captured CFIA agents on video condoning painful – and quite likely illegal – practices upon animals.

When charges are laid in these types of cases, they are usually brought against employees who commit actual harms, and rarely does a prosecution explore the institutional relationships that may have encouraged the abuse. It’s important to keep in mind that the undercover investigator in Chilliwack repeatedly alerted management about problems with the way the animals were being treated, yet nothing was done to stop the abuse. The protection of vulnerable animals cannot be focused solely on punishing animal abusers after the cruelty is inflicted. Rather, the focus must be the employers who permit abuse to flourish, or fail to dedicate enough time to the training needed to avoid it.

Canadian politicians repeatedly emphasize the importance of treating animals humanely but these words are starting to ring hollow. The Chilliwack case and others like it raise serious concern about this country’s dedication to protecting animals and its ability to bring charges against animal abusers in a reasonable time. It is absurd to imagine that the vicious abuse seen in Chilliwack should require over a year simply to decide whether charges are warranted, assuming that any ever come out of this horrific incident at all.

It is time to get serious about protecting animals, and the first step must involve taking a long, hard look at the relationship between those charged with investigating and prosecuting crimes of animal abuse.